“Libraries are all about inquiry,” says Valerie Jopeck, a former librarian and current education specialist for a large public school district in Virginia. But in this case, Jopeck is not talking about just online research or reading about animal behavior or electrical engineering.

Instead, Jopeck and her colleagues are talking about a new kind of inquiry-based learning cropping up in school libraries around the country—the opportunity for students to develop critical thinking skills by tinkering, designing, and building.

Exploratory, hands-on learning is also known as “maker education.” At “makerspaces,” learners have access to tools and supplies, including technological tools, for either open-ended or structured projects.

In recent years, some school libraries have taken on new identities as makerspaces, inviting students to do projects in the school library in addition to doing research or checking out books.

“A library is a safe space for students to learn and explore their own interests,” Jopeck said. “Hands-on inquiry fits in really naturally.” The library is also the only “content-facile space in a school building,” Jopeck said—one where the librarian can guide students on whatever learning journey they would like to take, regardless of subject matter.

When Jopeck worked as an elementary school librarian in Annandale, Va., she and other teachers on staff turned to making to cultivate persistence and resilience in their students. The educators had noticed that students became frustrated and gave up easily after making small mistakes on schoolwork. Jopeck had heard about another school librarian, Buffy Hamilton, who had integrated maker education into her work, and Jopeck thought a similar program could benefit the students at her school. With open-ended maker projects, trial and error is the name of the game. Students become accustomed to making mistakes and persevering.

Jopeck’s school began offering free afterschool maker sessions and maker project materials that students could check out of the library. The art teacher put together materials for puppet-making and storytelling. The phys-ed teacher assembled equipment to design circuit training workouts.

Jopeck’s school began offering free afterschool maker sessions and maker project materials that students could check out of the library. The art teacher put together materials for puppet-making and storytelling. The phys-ed teacher assembled equipment to design circuit training workouts.

With time, the students adapted to a new school culture that placed more value on persistence and risk-taking, applying the lessons from the maker projects to their other classwork, Jopeck said.

They learned that “if you put duct tape on the wrong way, the world did not stop revolving,” she said.

Jopeck, along with K-Fai Steele, Colleen Graves, and Buffy Hamilton led a session at the 2016 National Writing Project (NWP) annual meeting in Atlanta in November with a diverse group of educators. The session was geared toward school-based educators looking to integrate making into their curricula, with a focus on the school library as a prime site for making. Steele, an NWP program associate, developed the idea for the session in part from her work with The YOUmedia Learning Labs Network. The YOUmedia Network consists of “learning labs” in public libraries, museums, and community centers, where young people can drop in to work on digital media and maker projects.

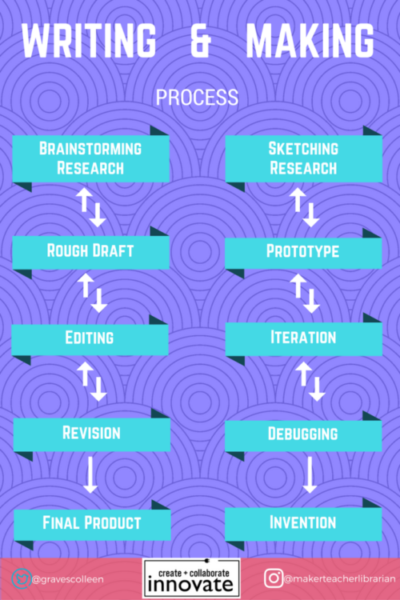

Many of the participants were English teachers. Graves—a maker, librarian, and former English teacher—discussed the parallels between making and writing and created a graphic that listed the similarities side by side.

A rough draft? Same concept as a prototype. Editing? That’s “iterating” in maker-ese.

The workshop leaders emphasized that the “making” umbrella is a large one. Some schools, like Ryan High School in Denton, Texas, where Graves works, offer maker projects using Makey Makey electronics kits or the programming language Scratch. Last year, Graves led a freshman English class on a start-to-finish invention literacy adventure. Using materials at the library and online, each student researched the inner workings of a device—from a water turbine to a guillotine—and attempted to make a miniature reproduction themselves.

In other settings with more limited access to digital tools, like the Annandale elementary school where Jopeck used to work, educators must figure out how to help the students build these same skills with less high-tech equipment—but it’s entirely feasible, Jopeck said. Parents regularly dropped off odds and ends from home construction projects or their workplaces. A first-grade class learned about plants, then “designed” and “prototyped” their own scientifically possible plant using regular crafting materials.

Makerspaces at any resource level can benefit from collaboration, Graves said, whether with a public library, a community makerspace, or a company whose designers will give product demonstrations to students.

“The libraries that form partnerships are doing the best work,” she said.

Still, there are hurdles. Another discussion group at the annual NWP meeting covered the common challenges of finding time for maker programming, professional development for librarians, or getting buy in from administrators or other teachers after a maker space has opened, for example. Although a library might be a natural setting for a makerspace, librarians often need support and time to reconfigure their roles.

But, say librarians, these investments are well worth it.

“Any space where youth are encouraged to write or experiment, whether they stick an LED on it or not, is critically important,” Steele said. “The maker movement is full of scrappy educators and people who can turn recycled materials into powerful learning moments.”

Photo/NWP

Leave a Reply